Pages 1 à 3 :

In the days of the religious wars of the sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries, French Huguenots were driven abroad to lands where they might earn their livelihood and might worship without molestation and without fear. A fresh impetus for this withdrawal was given at the close of the seventeenth century, when in 1685 Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes. No two countries were sought more eagerly by Huguenots than Holland—where Walloon churches testify to the number of refugees—and England, where (the French Hospital in London, and the various French churches there, and elsewhere in the country, bear similar witness. Many exiles, however, remained only a time in Holland and then proceeded to England. It is slight exaggeration to say that the revocation of the Edict of Nantes sealed the fate of French power in North America by dividing European countries upon a religious issue at a time when standing armies were growing in importance, and when the forces of England especially were strengthened by the military ability of many an embittered exile, or by that of members of his family. Of such John Ligonier, who rose to command the British army, and to an earldom, is merely an outstanding example.

Among this company was John Appy, whose family, like that of Ligonier, came from the south of France, probably from the village of Mérindol, in Provence. The present pastor of the Walloon church in Leyden says that he knew Appys at Merindol some thirty years ago. The name is to be found also in the catalogue of books at the British Museum, and a village of Appy is in the department of Ariège, near the Pyrenees.

Mérindol is in the country of those Vaudois, or Waldenses, who were massacred in 1545, and again in 1655, when Milton immortalized them in a sonnet:

On the Late Massacre in Piedmont

Avenge O Lord thy slaughter’d Saints, whose bones

Lie scatter’d on the Alpine mountains cold;

Ev’n them who kept thy truth so pure of old

When all our Fathers worship’t Stocks and Stones,

Forget not: in thy book record their groanes

Who were thy Sheep and in their antient Fold

Slayn by the bloody Piedmontese that roll’d

Mother with Infant down the Rocks. Their moans

The Vales redoubl’d to the Hills, and they

To Heav’n. Their martyr’d blood and ashes sow

O’er all th’ Italian fields where still doth sway

The triple Tyrant; that from these may grow

A hunder’d-fold, who having learnt thy way

Early may fly the Babylonian wo.

These sturdy Huguenots were, of course, in renewed difficulties at the time of the revocation of the Edict of Nantes; by 1698 they had been ordered into exile. Probably then the Appy family fled to Holland: in the second quarter of the eighteenth century they were well established in Amsterdam; the records of the Walloon church and library at Leyden list the birthday and the baptism not only of John Appy (whose meticulous account-books in the Huntington Library, California, and in the New York Historical Society respectively, are the cause of the present volume), but of several of his brothers and sisters. John was born in Amsterdam on February 12, 1725, and was baptized at the French church six days later. His parents were Peter Appy and Marianne Giguer. On August 17, 1736, « Pierre Appy, » together with his daughter, Marie, was received into the Amsterdam Walloon church, and of both is added « gone to London. » Young John Appy probably emigrated with his parents and his sister. As will be found later, an elder brother, Peter, went to sea in the same year and turned up in the colony of Georgia.

Nothing more is heard of John Appy until January 1, 1756, when he began the account-book now with the Loudoun Papers at the Huntington Library. From this folio volume it may be inferred that he was living by himself and was probably employed as a clerk in a government department. The Earl of Loudoun, lately appointed commander-in-chief in North America, engaged him as Secretary in February, 1756, describing him as, « the Son of a Broaken Amsterdam Marchant that was first an amanuensis to Major Cahine [?] that when he came to Ld Albermarles he was a Coppy Clark above Stairs that the great recommendation of him given to me was that he was a Drudge that could work for ever.«

If John Appy was so employed in London, presumably he had been educated in England, where he was regarded as virtually an Englishman

Pages 59 à 69 :

While Lord Loudoun was busy with the organization of his forces, an event occurred which might have become an important national incident, and must certainly have caused John Appy considerable perturbation—the detention in Philadelphia of his older brother, Peter, under suspicion of being a French spy. The matter was reported by John Stanwix, colonel of the first battalion of Royal Americans, commanding in Pennsylvania, to Loudoun, in a letter from Philadelphia dated April 20, 1757:

I am to trouble your Lordship with a pritty extraordinary affair that has taken up for two days the attention of the Govern’, Chief Justice & Attorney Gen & my self, viz a person taken up here as a Spy, whose examination I here inclose to your Lordship, the person has been to all Countrys, speaks most Languages well, on his examination appears a man of good sense & good art, land’d in this Country from Cape Francois in a very mean habbet & apparently in meaner Circumstances, his name Appy; towards the end of the Examination that he had a Sister kept a Boarding School at Chelsea; the Lady I know being one at the Governatees of the Blacklands school for younge Lady, my dawter being under her care, who I knew to be a Sister to Mr. Appy your Lordships Secretary, wch: lead me to ask this prisoner if he knew him; he said he had a Brother John, on which I show’d him his hand writing, wch: he assures us he knows well to be his hand; he has been in jail on. suspition of his being a Spy; have order’d him to be supply’»! with necessarys & Subsce: at two Shilings a day till your Lordship gives me orders what to do with him; for further particulars must refer to the Examinations and shall he most safe in waiting your Orders as any man’s Brother may be a Spy….

The papers enclosed give information not only as to Peter Appy himself, but as to the Appy family in general, indicating that they came from Provence, that they were people of education and accomplishments, and that they were undoubted Huguenots:

The Examination of Peter Appy of Amsterdam Merchant aged about Forty one Years taken before the Governor 18th April 1757.

The Examinant says that he was born at Amsterdam and is the son of a French refugee and lived there till he was Twenty one… That in the Year 1736 he went to Georgia, staid there about Sixteen Months and went thence to London with Dispatches from General Oglethorpe, after a short stay there of a few months he went to Paris where he staid till the beginning of the year 1740 … thence he went to Port L’Orient [Lorient] where he embarked for the French East Indies along with Captain St George and as his companion. In the East Indies he carried on a Trade for Three Years and was last at Bengal from whence he returned to Holland in a Dutch East India Man, staid there eight or ten Months and went thence to London where he staid till the Year 1746. That at the latter end of the Year 1746 he returned to Holland, was Midshipman aboard a Dutch Man of War, and in 1748 He went in that Quality into the Mediterranean, quitted the Ship at Leghorn and travelled to Genoa, to S’ Tropis’s Bay and from thence by Toulon to Marseilles; There he staid Three or four Months and then embarked in a Snow [a small sailing vessel resembling a brig, with main, fore, and supplementary trysail masts] belonging to Mr. Frescheint to Martineco, where he moved in the beginning of the Year 1750. that he staid there till the beginning of the Year 1754, and was employed to Instruct a Young Gentleman called Mr. Paix but being suspected to be a Protestant he sailed from thence to St. Eustatia [a Dutch island in the West Indies] & continued there about four Months; then went to St Kitts recommended by the Merchants of Statia to Mr. Lausac Mr. Pringle and Mr. Welsh. That he saw Captain Fabri at Statia and again at St Kitts and dined with him at his own House there. From St Kitts he went to St Thomas’s lived there a Year with one Mr. William Wildhagen and was concerned in a private Trade to St Domingo and in a Voyage there was taken by a French Guarda Coast and carried to Cape Francois [Hayti?]. That he staid fifteen Months there, being Sick five Months of the Time and obliged to sell his Cloaths Gold Watch and other Things, That he went from thence to Georgia in the, Sloop Isabella, Captain Martin. From thence to South Carolina and in January last returned to Georgia. That in the month of March he took his Passage in the Dispatch Captain Filemon Fenix to New York, from which place he came in the Stage Waggon and Boat to Philadelphia in hopes of seeing an old acquaintance that-he formerly knew at Georgia, one Mr. Burnsides who is lately died, and of getting into some way of living either as an Usher in some Boarding School or by teaching French. This Examinant further says that at Cape Francois he was acquainted with one Joseph Hossey a Carpenter of this Town who gave him two Letters, one for his Wife and the other for his Father in Law Robert Eastbum, that this last was worn to pieces in the carriage but the other he delivered to Mrs Hannah Hossey.

Being asked if he was ever at Providence [probably the West Indian island of New Providence] he answered in the Negative, but that he had told Mrs Hossey he had been there, giving this as an Excuse for her Letters being so much handled. Being asked if he ever wore the French Uniform or a Cockade, at Statia; he said never, that he was often gaily dressed and had on very rich Cloaths when he came to Statia. Being further asked if he ever had a French Commission he said he never had.

Peter Appy

Examined before me

William Denny [Governor of Pennsylvania]

Peter Appy being further Examined says that he has a Sister called Mary who kept a Boarding School at Chelsea & was in Partnership with one Mrs Poignan when he last left London about Ten Years ago and that he has a Brother called John who may be now about Twenty Seven Years of Age.

The Mary Appy here mentioned is undoubtedly the sister who went to England from Amsterdam in 1736 with her brother John and their father. When, on the’ nineteenth of April, 1756, John Appy paid two shillings and fourpence for coach hire and turnpike to Chelsea, he was most probably going thither to say good-by to his sister before his departure for New York.

The first Earl of Egmont, who was associated with the government of Georgia, has left in his diary for 1736 a brief description of the delayed arrival of Peter Appy in London bearing the despatches from Oglethorpe. Even at that time Charleston, South Carolina, seems to have been a delightful place, and Appy showed the family liking for sociability. The « Mr. Westley » referred to, is, of course, Charles Wesley, who was returning to England and to Methodism. On December 8, 1736, the earl wrote:

That Mr. Oglethorpe sent us large accounts of his proceedings, which ought to have been with us three months ago, being sent by Mr. Apie, but this gentleman loitered his time at Charlestown, where he was to take shipping, and at last came away in the same ship with Mr. Westley, so that they arrived together, and even though now here, he has neglected to bring or send us the packets he was charged with.

This has proved of great detriment to us, and I suspect the Carolinians prevailed on him to defer his departure till after they should send over their remonstrance against us.

Three days later this entry was followed by another: « The packet brought over by Mr. Apie, and so long detained by him, was brought at length to the Board, but they are mostly duplicates of what we found in the journal book.«

The testimony of Peter Appy shows the adventurous life of one who suffered (in a material way, at least) because of his religious faith. From a modern point of view, it is strange that he was not questioned as to his activities in Paris just before 1740.

William Shackerly, Esquire, Agent and Superintendent of the Transports in North America, explained to Governor Denny that he had been a fellow passenger with Peter Appy on the « Stage Boat » from New York to Amboy. By 1757 it was possible to set out from New York to Philadelphia at Whitehall stairs: on Mondays, in a boat commanded by James Magee; or on Thursdays, in one commanded by Daniel O’Brien—both of these vessels « extraordinary well fitted for Gentlemen, Ladies and others, as Passengers. » Leaving Perth Amboy, New Jersey, travelers usually went by stage to Burlington, where « boats constantly attend the Carriage of Things to Philadelphia. » Shackerly said that Appy had entered into conversation with him, saying he had been in London, where he knew intimately several persons of rank, among them the Duke of Newcastle, the family of the late Earl of Pomfret, and especially Captain Fermor of the Royal Navy. Thomas Fermor, Lord Leominster, had been created Earl of Pomfret on December 27, 1721. His second son, William, had been in command of the Nightingale and the Experiment. He died at sea in 1758.

Peter Appy had also mentioned having been in some of the French, Dutch, and English islands, and that « he had kept the best Company in all places where he had been but was now reduced. » Shackerly added that Appy the traveler did not seem to speak as good English as Appy the prisoner.

Samuel Bonsai, keeper of the Philadelphia tavern whither Appy had gone on April 15th, « out of the Trentown Stage Boat, » having lain on board all night because he was a stranger and did not care to come ashore after dark, deposed that Appy declared he had been three times taken by the French, who had stripped him of his possessions. He exhibited three letters, two of them torn, which had been opened by the French, and a paper which he said contained an account of the taking of Oswego. Appy had asked a neighbor of Bonsai’s, Thomas Prior, to lend him the newspapers for the past year.

The testimony of the next witness before the governor, Anne Titterbury, wife of the keeper of a public house, is interesting because it shows the indifferent political morality of the mid-eighteenth century: Americans, if it were to their pecuniary advantage, were often as willing to trade with, as to fight against, the French. The letter which Appy brought from Joseph Hossey, the ship’s carpenter captured by the French and carried to C/ Francois, was included with Anne Titterbury’s deposition, and urged Mrs. Hossey to join her husband at the cape, where she could live luxuriously:

My Friend Appy is agoing to Georgia [Hossey wrote], from thence to he intends to come to Philadelphia; my dear use him with kindness for he is my Friend; he will inform you of some of my Misfortunes; he is a Gentleman by birth and behaviour; loving Wife watch all Opportunities to write to me; my dear, if you have any notion to come here to live write to me, my dear, if you have any notion to come for you immediately [this was penned on April 14, 1756, when France and Britain were officially at peace], I have offers made to me daily. I can have an hundred Pound a Year and everything found me and you, and two Negroes to tend upon you and me, a House and Furniture…

Mrs. Titterbury narrated that Appy came to her husband’s public house and enquired for Mrs. Hossey, « saying he had a Letter for her from her husband … at Cape Francois, where he did very well, wore his Laced Hat and had good Encouragement from the Governor of the Place. » When Mrs. Hossey arrived, and Peter Appy had given her the letter, she asked him how it happened to be torn and opened:

Madam sayd Mr. Appy you woud wonder much more that ever you got the letter at all, if you knew what had happen’d, and appeared to be Angry; she then asked him where he came from, and he answered he forgot and would say no more.

After Mrs. Hossey’s departure, Appy told of having been taken and retaken by the French, and said:

Mrs. Hossey did not know what harm she had done herself but when She reads the letter she will see it and come to me again; She may live like a Queen, have two Negroes to wait upon her, any House she shoud chuse on the Island, Four Pipes of Wine a Year, and a Yearly Pension; and that he cou’d have helped her to Forty Pounds from an honourable Gentleman in this City with whom he had been that Morning, and who promised to give her the Money. Then she enquired the Gentleman’s Name, but he said in an angry manner, stamping upon the Ground, his Name is buried here and shall not be mentioned since she has used me so ill. That he had orders, but whether before the War or since she cannot say, for a Sloop, in which he was to be half concerned … to bring Mrs Hossey over.

Bartholomew Fabre, captain of the transport Oliver Cromwell, apparently had been the cause of Appy’s detention, for he « thought there was something suspicious in the Man and therefore mentioned it to some Gentlemen of his Acquaintance in this City. » He describes how he had first seen Appy in Statia, richly dressed and with the appearance of a gentleman of distinction, and later at St. Christopher. Appy told him he had come thither on business, and, finding out that Fabre hailed from Marseilles, asked him if he knew any Appys there. Upon Fabre’s answering that he did, that they were very able merchants, Appy replied that they were his relatives. « A few days afterwards Mr. Appy left his Trunk in a Tavern and privately went off as was imagined for want of Money. » Fabre saw him, but not to speak to, some months afterwards at St. Thomas’s, and then not until a few days previously, when Fabre was « surprized to find him make such a mean appearance; upon which he asked him how he came into such distress; he answered by misfortunes and that he had an inclination to go back to Holland. That he always took him for a French Man till that day, when he told him he was a dutchman.«

The master of the vessel that brought Peter Appy from Georgia was able to give facts about him which must have reassured the authorities, they indicated not only his association with one of the most prominent men in the south but his staunch Protestantism, for he was a freemason. Telamon Phenix (Philemen Fenise in the account) was in command of the square-built sloop Dispatch, of twenty tons and a crew of five, which had been built in New England in 1751 and was owned by Nathaniel Allyn. She had left the Virgin Islands at the end of November, 1756, with a cargo of three hogsheads and eight barrels of sugar as well as sundry European goods. Calling at Georgia, Phenix, at the request of one Huson, merchant and planter, took Appy aboard as a passenger for New York, his fare of three pounds being paid by the local masonic lodge. « Huson » was apparently Sir Patrick Houston, Baronet, who had succeeded in 1751 to a title created on February 29, 1668.

Sir Patrick had been Comptroller of the Customs in Glasgow and chamberlain of Kinneil, but he had emigrated to America about 1740. Intending to settle in the new world, he had taken with him the portraits of his grandfather and of his parents. At Savannah he became President of the Council of Georgia. Although he came into the baronetcy in 1751, he did not at the same time inherit the family estates. He died on February 5, 1762, at the age of sixty-four. In the cemetery at Savannah are memorial inscriptions to him and to his wife.

Phenix said that about ten days before sailing he met Appy, who told him he had been a partner of Sir Patrick Houston. On the voyage of five days to New York, the passenger had been reticent about himself; Phenix concluded that, as Appy was poor and shabby and said he had business in Philadelphia, he was going thither to seek help from the freemasons. Appy stayed about three weeks in New York, where he was clothed by one Abraham Sazzadas, a fellow passenger who had been recommended for permission to carry a cargo of provisions to Georgia. Sazzadas ordered Phenix to give Appy forty shillings to take him to Philadelphia.

When Appy, questioned as to the person with whom he had business, mentioned only the well-known Moravian, the late Mr. Burnside, Governor Denny and Colonel Stanwix were evidently satisfied; nevertheless Stanwix wrote to Lord Loudoun on April 30th that he would send Appy to New York on the next transport to leave Philadelphia.

The mystery is increased by a letter written from John Appy in New York to a French prisoner, Monsieur Picard, on May 2nd:

La Lettre que vous m’avez fait l’honneur de m’envoyer, de mon Frère, m’a fait un Sensible Plaisir, il y avoit long tems que je n’avois eu de ses Nouvelles, et bien plus long tems encore, que je ne l’aie vu. Il vous recommande dans sa Lettre, en Ami ; mais vous ne me dites pas en quoi Je puis vous être utile ; Si vous étié icy, Je ferois de mon mieux pour rendre votre Captivité le plus agréable qu’il me seroit possible — cela n’étant pas, marqué moy si en écrivant au Gouverneur on pouroit vous procurer quelque avantage, Je feré avec plaisir tout ce que dépendera de moy.

J’ai L’honneur d’être,

Monsieur, Votre très humble & très Obt Servr.

J: Appy

The muster-roll of the Nightingale for June 20th shows that Peter Appy was carried as a supernumerary to Canada, where he was « discharged by order » at Halifax on July 15th. Is it possible that he had been a secret agent of the British, especially useful because of his French origin and his roving life? Certainly the authorities treated him with consideration.

Pages 160 à 169 :

By the first of October General Amherst was seriously concerned about the health of his secretary; he says in a letter to General Gage, then Governor of Montreal, « Appy has been in a most miserable way, continually in torment, and appearances very bad; I fear it will end ill with him, » to which he adds, in a letter written five days later, the opinion of the surgeon at the general hospital, James Napier, « I Acquainted You of the miserable State poor Appy has been in; Mr. Napier has been with me to day and thinks he can’t live, » concluding on October 13th, « Poor Appy is alive but in a very bad way, and I fear but little hopes of his Recovery.«

The doctor and the general were true prophets: John Appy died on Wednesday, October 14th, the day he became the father of a daughter, to be named Elizabeth after her mother. Of these events Amherst wrote on October 22nd to Colonel Ralph Burton, who was acting as Governor of Three Rivers: « I have lost poor Appy, who Dyed on the 14th after Suffering great Torment; his Wife brought to Bed, almost at the moment of his Death; but She and the Child are likely to do well.«

The New York Mercury for Monday, October 19th, contains the notice that there had

… departed this Life, in this City John Appy Esq; Judge advocate, and principal Secretary to his Excellency Sir Jeffery Amherst, Esq; K.B. a Gentleman of a fair character and universally beloved: His remains were decently interred in Trinity Church the Friday evening following.

Amherst is called Sir Jeffery because already he had been created a Knight of the Bath, though he was not to be invested with the insignia of the order until the twenty-fifth of October. This, the first investiture in America, was held by Governor Monckton with fitting pomp at the camp on Staten Island.

In Albany, on June 10, 1758, John Appy had made his will, leaving his real and personal estate to his wife, with the exception of twenty guineas each to his two executors: Peter Appy, of London, his father, and Abraham Mortier, described as « my good friend. » In connection with the probate of the will, Peter Appy « of the parish of St. Stephen Coleman Street, » appeared before the surrogate, William Burrell, in London, on April 27, 1763. In America the will was sworn to at the end of August, 1764, by James Robertson, Lieutenant-Colonel of his Majesty’s 15th Regiment, and Gabriel Motiern, Secretary of the Forces. Appy was succeeded as Secretary by Arthur Mair, and as Judge Advocate by Captain H. T. Cramahé.

When the value of money in 1761 is considered, it will be seen that Appy left his dependents fairly comfortable. Writing to Gage, on November 16th, 1761, Amherst comments, « Poor Appy is no More. I am not Sure but I have already Acquainted You of his Death; he was no less Punctual in his Private Affairs than in his Official; he has left bout 3000 £ to his widow, who has a little Girl to take care of.«

For a decade after the death of his son-in-law, Abraham Mortier was a well-known figure in New York. No less inveterate a playgoer than Appy, Mortier patronized the first New York playhouse, founded by David Douglass in August, 1761. Then as now aid in producing plays was given by private individuals, but there was often in these productions an intimate touch absent from the modern commercial theater (although still existing in university, and in other small communities) the comparison or the contrast of a stage character with that of a local celebrity. « Thus, when ‘Laugh and Grow Fat’ appeared, the public said it well fitted the case of Abraham Mortier, the paymaster of the British army, and the projector of Richmond Hill house. He was a cheerful old gentleman, but the leanest of all human beings—almost diaphanous.«

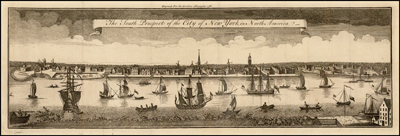

Richmond Hill Farm, a beautiful place on the outskirts of the city bordering the Hudson, was leased by Mortier from Trinity Church. The estate was later associated with George Washington; President John Adams, when Vice-President, and Aaron Burr. Mrs. Adams has left a somewhat ornate description of the grounds, from which, however, it is possible to realize something of their charm:

In natural beauty … it might vie with the most delicious spot I ever saw. It is a mile and a half distant from the city of New York. The house stands upon an eminence; at an agreeable distance flows the noble Hudson, bearing upon its bosom innumerable small vessels laden with the fruitful productions of the adjacent country. Upon my right hand are fields beautifully variegated with grass and grain, to a great extent, like the valley of Honiton in Devonshire. Upon my left the city opens to view, intercepted here and there by a rising ground and an ancient oak. In front, beyond the Hudson, the Jersey shores present the exuberance of a rich, well cultivated soil. In the background is a large flower-garden enclosed with a hedge and some very handsome trees. Venerable oaks and broken ground covered with wild shrubs surround me, giving a natural beauty to the spot which is truly enchanting. A lovely variety of birds serenade me morning and evening, rejoicing in their liberty and security.

The popularity of Mortier is reflected in the notice of his death printed by the New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury for January 6, 1772:

On Sunday Night the 29th of December, died at his House near this City, in the 60th Year of his Age, Abraham Mortier, Esq: Pay-Master General to his Majesty’s Forces in North America, a Gentleman of a most amiable character, and eminently distinguished for the Uprightness and Integrity of his Conduct in his Office and all his Dealings: He was as universally esteem’d as known, and is generally lamented. His Remains were on Tuesday Evening inter’d in Trinity Church-Yard, with all the Solemnity and Respect that could be shown them, both by the Gentlemen of the Town and Army, a numerous Company of whom attended.

He was succeeded in his office by T. Burrow. By his will, dated March 28, 1769, Mortier left his brother David, of London, and Goldsborow Banyar his executors. His wife also died in New York, leaving a will of September 30, 1786, proved April 30, 1787.

After the death of John Appy, his widow appears to have lived with her mother and her stepfather. A letter of Abraham Mortier to Horatio Gates, written on November 23, 1763, when Gates had come back from England to settle in Virginia near his friend George Washington, joins Mrs. Mortier and Mrs. Appy in the good wishes sent to Gates. On February 4, 1767, Elizabeth Appy married again, this time Goldsborow Banyar, a native of London who had been brought to America in 1737, at the age of thirteen, and who was one of John Appy’s executors.

Before he had passed his twenties Banyar had become Auditor-General of New York, and for some years he was clerk of the council of the province. By 1752 he was Register of the Court of Chancery, and the following year a Judge of Probate. He is one of the interesting men of his period, because his life (he died on November 4, 1815) includes the time of the French and Indian Wars, of the American Revolution, and of the founding of the United States. A friend of his later days as a resident of Albany has described his career:

At the breaking out of the revolution, very naturally, and the prospect considered, very wisely, he took sides (but not arms) with the mother country. He was a royalist in feeling, and doubtless in principle—the feeling, it is believed, underwent no change; the principle, in the course of time, became temperately, and I may add, judiciously, modified by his interest. He had, while in his office of secretary, obtained from the crown many large and valuable tracts of land. These lands were the sources of his wealth. … He preserved his character from reproach, on the other side of the water, and his lands from confiscation on this. He became an American when America became triumphant … and finally, without abating a jot of his love for the land of his birth, came quietly into our political arena under the banner of Mr. Jefferson! … He was no American at the commencement of the war, but an Englishman, born and bred. … Yet he took no part—gave no aid, and but little comfort to the enemy, for when secretly applied to for advice, he sent by the messenger a basket of fruit—and when for information, the return was a basket of eggs! …

He must have been somewhat about three score and ten years of age when I first saw him in the streets of Albany. He was a short, stout built man, English alike in form, in character, and in aspect: and at the period to which I refer, infirm, gouty, and nearly blind, but still sound in mind and venerable in appearance. The colored servant by whom he was led, was no unimportant personage. … What was not a little remarkable was that Peter resembled his master in almost every particular, save his gout and his blindness. He was of die same height and make, as well dressed, nearly as old, and quite as grey. He was, moreover, as independent and as irritable. At a little distance it was indeed difficult to tell which was master and which was man.

Nothing could be more amusing than their conversation and disputes when moving together, arm in arm, down Pearl street and across State, to Lewis’s tavern—a haunt to which they resorted daily, whenever the weather would permit.

… In crossing State street one day, on their return from Lewis’s [the author overheard]: Peter … you’re leading me into the mud. There’s no mud here, says Peter. But I say there is, retorted the old man firmly. I say there aint, said Peter. D—n it, sir, said the old man, giving his arm a twitch and coming to a full halt, don’t you suppose I know the nature of the ground on which I stand? No, says Peter, don’t spose you know any such thing; you ony stept one foot off the stones, tha’s all. Well, well, come along then; what do you keep me standing here in the street for? I don’t keep you, said Peter; you keep yourself. Well, well, come along, said the old man, and let me know when I come to the gutter. You arc in the gutter now, said Peter. The devil I am! said the old man; then pausing a moment, he added, in a sort of moralizing tone, there’s a worse gutter than this to cross, I can tell you, Peter. If there be, said Peter, I should like to know where ’tis; I have seen, continued Peter, every gutter in town, from the ferry stairs to the Patroon’s, and there aint a worse one among ’em all. But the gutter I mean, said the old gentleman in a lower tone, is one which you cross in a boat, Peter. ‘Tis strange, said Peter, that I should never have found it out— now, lift your foot higher or you’ll hit the curb stone—cross a gutter in a boat, ejaculated Peter, ’tis nonsense. ‘Tis so written down, said the old man. Written down, said Peter; the newspapers may write what they please, but I don’t believe a word on’t. I’m thinking, said the old man, they put too much brandy in their toddy there at Lewis’s. I thought so too, said Peter, when you were getting off the steps at the door; and since you’ve mentioned that boat, I’m sure of it. What is that you say? said the old man, coming to a halt again, and squaring himself round; you thought so did you? what right had you to think anything about it? I tell you, Peter, you are a fool.

Since Mrs. Banyar had married two men, each of whom held office under the Crown, it is not surprising that her daughter, Elizabeth, should have wedded an Irish officer, Lieutenant William Jephson, of the 28th Foot, while New York was occupied by the British forces during the War of the Revolution. The marriage took place in Trinity Church one day between March 18 and 24, 1777. As William Jephson was heir to an Irish estate, The Castle, Mallow, County Cork, the match was presumably a brilliant one for Miss Appy. Her husband was promoted to a captaincy on January 8, 1778. After 1780, he transferred from the infantry to the 17th Light Dragoons, which, under the later title, 17th Lancers, has been one of the noted regiments in the British Army.

The only child of Mr. and Mrs. Jephson, William Henry, was born in New York on April 11, 1782. When his father went back to England after the peace of 1783, the boy was left in America with his mother. Soon the elder William Jephson inherited The Castle, Mallow; whereupon he married bigamously Emma Butler, sister of the then Viscount Mountgarret, who died in childbed in 1786. Although the will of Martha Mortier is so worded as to suggest that Elizabeth Jephson might be divorced from her husband, apparently that divorce was never granted, and, on January 31, 1799, William Jephson, then a major, married Louisa Kensington of Blackheath. The marriage was chronicled in the Gentleman’s Magazine as of social importance. In the same year a son was born, Charles Denham Orlando. In 1802, William Jephson became a lieutenant-colonel in the army, and evidently the following year the story of his bigamous marriages was known in Mallow, for his wife and child left his house, asking protection from a neighboring landlord and friend, Sir James Cotter, Baronet. In spite of his intimacy with Colonel Jephson, Sir James challenged him to a duel with pistols. The colonel, wounded, confessed what he had done, and was obliged to leave Ireland, at least for a time. After 1803 he disappears from the army lists until the War of 1812, when he is entered as Barrack Master at Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1813. Late in that year he returned to England in the Lapwing, packet, and, soon after his arrival, died at Milford, aged fifty, on October 12th.

Since the former Miss Kensington was esteemed by her Irish friends, she remained in Mallow to bring up her son. As young Denham grew to manhood he felt he had no wish to be known only by the name Jephson; therefore he added to it that of the former Elizabethan owner of the Castle, Sir Thomas Norreys, calling himself Charles Denham Orlando Jephson-Norreys.

John Appy’s daughter, Elizabeth Jephson, remained always in the city of her birth, where she died on Sunday morning, October 9, 1808, at the age of forty-seven. Her son, William Henry, was for a short time in business with Joseph Reade, under the firm name of Reade and Jephson. Having only unpleasant associations with Ireland, he allowed the cutting of the entail of the Irish property, that his half-brother might succeed to the estate. William Henry Jephson died at 24 East 33d Street, New York, 011 March 11, 1867.

Such is the brief history of John Appy’s family circle after 1761, all of whom stayed in North America.

His friends and associates in the army had various careers. The later life of Lord Loudoun has been outlined already. General Abercromby, in accordance with the rules of seniority in the army, rose to the rank of major-general. He passed the greater part of the last twenty years of his life at his family place, Glassaugh, Banffshire, Scotland, where he died on April 23, 1781. Sir Jeffery Amherst returned to England in 1763, and was promoted a lieutenant-general in 1765. He became a close friend of King George III, by whom he was raised to the peerage as Baron Amherst, in 1776. Early in the War of the Revolution he was urged to supersede General Gage as commander-in-chief in North America; however he declined, and never took arms against his former associates in the colonies. Nevertheless, as Lieutenant-General of the Ordnance, he was virtually in control of army operations; he was consulted on all matters connected with the campaigns in America. After France sided with the thirteen colonies, he became commander- in-chief of the army in name as well as in fact. His last conspicuous act was when he suppressed the Gordon riots of 1780 with promptness and vigor. He died on June 3, 1787, the peerage descending to his nephew, William Pitt Amherst.

After 1761 Colonel Haldimand gave further distinguished service to the country of his adoption: as lieutenant-general he was for a time commander-in-chief in North America, and he succeeded Sir Guy Carleton in 1777 as Governor of Canada. In this office he roused the anger of French Canadians who sympathized with the rebellious colonists to the south. He returned to England in 1784, where he was created a Knight of the Bath. He died at his birthplace, Yverdun, Neuchatel, Switzerland, on June 5, 1791.

Note : Jean / John APPY est né à Amsterdam le 12 février 1725 ; il est le fils de Pierre APPY (né à Lacoste le 11 avril 1686) et de Marianne GUIGUER. Il descend donc de la branche des APPY de Lacoste.